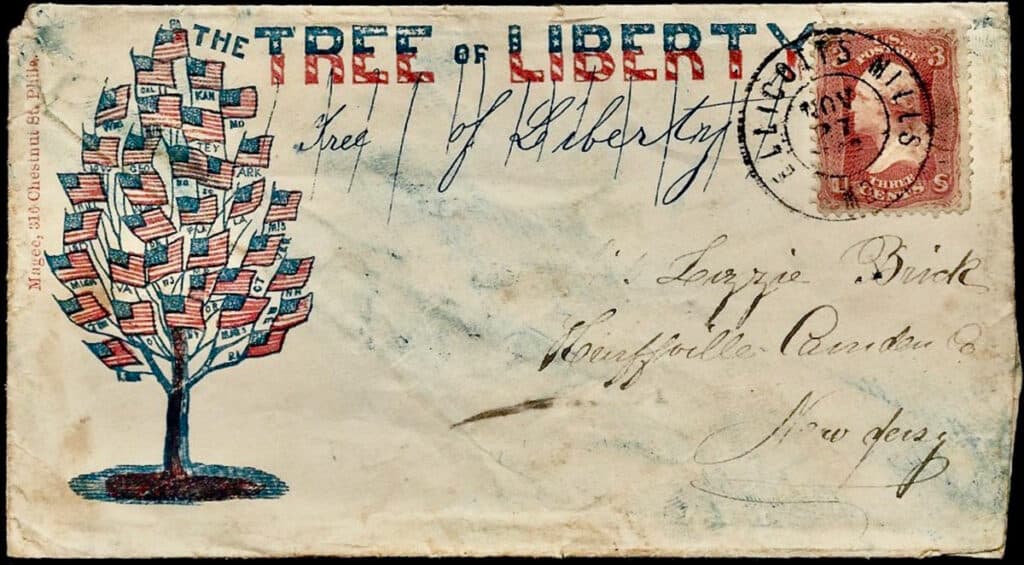

As a society, we tend to be all agog over social networking systems — just not in connection with the Civil War and the pre-electricity life of 160 years ago. But President of the Gloucester County Historical Society and Westchester University Professor James M. Scythes has put together a fascinating book documenting an unusual social network of Civil War letters between 16 Union Army soldiers and a young Sunday school teacher, Lizzie Brick, from Hurffville, New Jersey.

Published by Kent State University Press, the book — Letters to Lizzie: The Story of Sixteen Men in the Civil War and the One Woman Who Connected Them All — is based on a collection of letters from the Historical Society’s archive passed down from families in Hurffville, Mantua, Mullica Hill, and Deptford.

The 120-year-old Gloucester County Historical Society maintains one of Southern New Jersey’s largest genealogical collections as well as extensive collections of Civil War era military records, letters, diaries, photographs, uniforms, weapons and equipment.

The narrative and documentation of Scythes’ book pivot around Lizzie Brick, who exchanged Civil War letters with 16 men who enlisted in the Union Army from the Gloucester Country area and marched off to 11 different military units scattered across the war zone.

“This correspondence is unlike any other large collection published to date,” explained Scythes in his presentation at last week’s Authors’ Day event at the Historical Society in downtown Woodbury. “Many collections of Civil War letters have been published over the years, but those works typically contain correspondence between just two individuals. This collection of coordinated letters differs by presenting the events of the war from multiple perspectives, offering us a chance to view the war through the experiences of 16 men and one young lady.”

Teenage School Teacher

The Civil War letters span the entire timeline of the war with young Lizzie Brick at the center. Just graduated from Bordentown Female College, Brick was an avid letter writer and, in her late teens, the same age of many of her correspondents. While two of those male writers appeared to have romantic feelings for her, the rest were consistently more interested in knowing what she was seeing on the home front or hearing from her about what soldiers told her about friends and family members scattered across military units engaged in the fighting.

Ultimately, three of the 16 men were killed in the war, several more were wounded, and two more survived but never returned to the Hurffville area.

The incoming Civil War letters to Lizzie detailed an array of poignant and horrific wartime sights and experiences. Some examples:

William Carr, a member of Lizzie’s church who enlisted in an infantry unit, wrote of being wounded during the Battle of Fredericksburg as massed Union forces made frontal assaults against Confederate fortifications studded with cannon in one of the bloodiest battles of the war. It was a Union defeat with 12,000 casualties. Thomas Wick, who was in the same Fredericksburg battle, told her it was “a blunder in our officers taking us in right under the mouth of their canons to be slaughtered like hogs. The boys are all discouraged.”

Battlefield Burial Duties

Thomas Clark described the combatants’ burial duties. “After the battle is over, we pick up shovels and dig holes and throw [the bodies] in and cover them up. We don’t have any funerals preached out here. We are satisfied to [just] get [them] covered up and out of sight.”

William Chew, who was in the Battle of Fair Oaks on the outskirts of Richmond, where the Union Army suffered more than 5,000 casualties, described the aftermath. “Here is the dead buried all around me, four and five together in a grave. Oh, Lizzie what an awful looking place this was after the battle was over.” He indicated heavy rains exposed the bodies in their shallow graves and the air was laced with a putrefying stench.

Theodore Brick, a relative, wrote from the Union camp at Falmouth, Va., telling Lizzie of the horrific scene outside the military hospital.

“Pile of Legs and Arms“

“There was a pile of legs and arms laying outside of the door,” Brick wrote. [It was] “enough to make the stoutest heart quack and blanch with fear.” He told her he would rather be “killed dead… than be wounded and maimed in that way.” In another of his Civil War letters about Christmas day in 1862, he wrote, “I was on picket [and] was thinking of home… but there I was by the fire at night in the woods… There is a big difference between [a home meal] of roast turkey and [one of] hard crackers and pork… There is no delicacies to be had down here.”

Thomas Clark, a Hurffville wheelwright before joining the infantry. wrote about the ugly debates with some northerners who resented “fighting for the negroes.” Clark told Lizzie that the government should allow African Americans to join the Army so “they could fight for their freedom.”

Benjamin Young, who was Lizzie’s uncle, fought in the Battle of Antietam where over 2,000 Union soldiers died and more than 9,000 were wounded — he was one of those, having been hit by shrapnel. His Civil War letters explained how after the battle ended, he witnessed some Union and Confederate soldiers helping each other with their wounds. “All animosity was then forgotten,” he wrote. “Even if it was only temporary.”

“We Sleep in Our Clothes”

Isaac Clark detailed camp life. “We sleep every night in our clothes, overcoats and all, with our muskets by our side, as we expect to march every moment,” he said. “We are throwing up an entrenchment in the heights that commands the roads leading to Washington. We are under marching orders and expect to leave this place soon but there is no telling where. With six days of rations in our haversacks and 60 rounds of cartridge, I will write again when we get to our destination.”

Scythes noted the difficulties of working with such a large body of handwritten letters from an era when low literacy or illiteracy were widespread. The task was further exacerbated by the fact that these missives were penned amidst the most frantic and stressful kind of battlefield conditions. He spent years studying the documents through magnifying glasses as he transcribed them.

“Most letters contain numerous grammatical errors,” Scythes said. “The spelling is atrocious. Punctuation and capitalization were rarely used. Nevertheless, these letters are really important because they provide us with valuable insights into the conflict. Some historians think such letters by common soldiers are frequently more powerful than those written by their educated counterparts.”

Struggling with Cursive Script

The project also made Scythes realize that many of the college students in his history classes — who came of age in a time when electronic screens and keyboards rule all personal communications — had never learned or practiced cursive writing.

“They don’t know how to read cursive script and after I gave a class presentation, they couldn’t read any of the letters I transcribed,” Scythes said. “It made me understand that we have a whole group of new historians that aren’t going to be able to read hand-written letters and documents from the 19th century and much of the 20th century.”