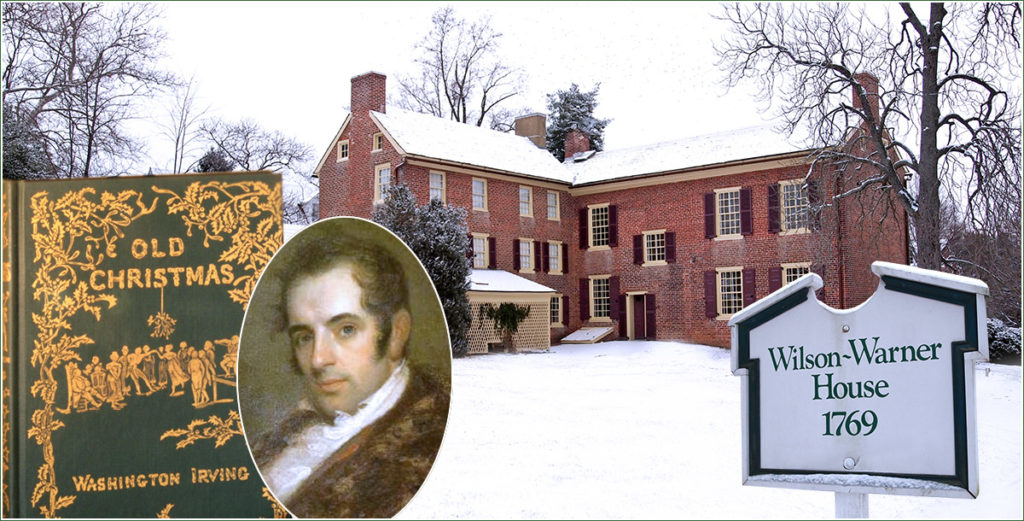

The most striking personal discovery in Brian Miller’s research aimed at turning Delaware’s 18th-century Wilson-Warner House into an exhibit about Washington Irving’s literary work and its impact on American Christmas customs was peacock pie.

“I loved the idea of a huge coffin pie trimmed out to look like a grand bird,” said the assistant curator of the Historic Odessa Foundation. “I wasn’t previously aware of the amazing history of peacock pie as the centerpiece of English holiday feasts going back to the time of Henry VIII; it appears in paintings all through the 17th and 18th centuries.” It was also a centerpiece in the Irving stories on which the Odessa “Literary Christmas” tour of a few years ago was based.

The Historic Odessa Foundation operates a village-like cluster of five 18th- and early 19th-century historic houses in northern Delaware. For ten months of the year, those structures are furnished and interpreted according to the documentation left by their original English Quaker occupants. But each November and December, one of them is completely emptied of its furnishings and turned into a historically-curated walk-through experience exploring a holiday literary theme.

Over the last quarter century, these unique holiday exhibits have celebrated works including “A Visit From Saint Nicholas,” “The Nutcracker,” and “Jane Austen’s Christmas.”

Bringing a literary theme to life

Miller was in charge of selecting, researching and physically bringing a literary theme to life as a historically accurate holiday exhibit. Along with the coherent narrative used by docents to guide visitors through the display, he creates appropriate room settings using period furnishings and artifacts from the Foundation’s own extensive holdings as well as those borrowed from other regional museums, libraries, universities and private collectors.

“We’re not just making pretty scenes,” said Miller, who is assisted by five other Foundation members in designing and executing the annual project. “There’s an educational aspect running through all of this. Visitors can enjoy the Christmas atmosphere of the house at the same time they learn something about the history of American holiday traditions.”

“In this case,” he continued, “we called it ‘An Old English Christmas of Washington Irving’. I think we all know about ‘The Night Before Christmas’ or Dickens’ ‘Christmas Carol,’ but Irving’s earlier work has been somewhat lost in terms of the popular culture’s understanding of where our modern holiday customs came from. The essence of what most people today recognize as a ‘traditional’ American Christmas is, in many ways, a takeoff on the Yuletide rituals of 17th-century English country life that Irving first documented for Americans in the early 1800s.”

Medieval Christmas

The story of both Irving’s legacy as well as this Odessa exhibit begins centuries ago during England’s medieval era when the celebration of Christmas was a highly popular and joyous occasion — indeed, sometimes riotously so. The feudal country estates that functioned as self-contained agrarian communities with their own populations of noblemen masters, workers and servants, developed a rich and colorful collection of rituals that transformed Christmas Eve and Christmas day into merry festivals of feasting, fellowship, gift-giving and games.

But in the mid-1600s, as a result of religious, economic and political turmoil, many of the activities long associated with the public observation of Christmas were banned throughout the kingdom; ultimately, Parliament even imposed punishments on merchants who closed their stores on December 25th or people who attempted to decorate their churches with traditional Yuletide greens.

During the next two centuries, Christmas in England and its colonies withered to become a minor event within the twelve-day mid-winter holiday season that became known as “Twelfth Night,” even as some activists continued to decry the “war against Christmas” and defied the bans on the old traditions. This was particularly true in the relatively isolated communities of England’s country estates.

Twelfth Night rather than Christmas

When they crossed the ocean to settle North America, the British brought their culture’s holiday battle with them; the Colonial society that declared its independence from England in 1776 and elected George Washington its first President in 1788 was largely one that celebrated Twelfth Night rather than Christmas.

The literary prodigy whose work would ultimately begin the undoing of that cultural fact was born to a New York merchant family in 1783 as that city celebrated the official end of the Revolutionary War. He was named “Washington” Irving in honor of the nation’s greatest hero.

From an early age, Irving developed an interest in holiday traditions, particularly those of the Dutch communities along the Hudson River where he lived for a time as a teenager. The Netherlands’ “Father Christmas” figure was featured prominently in the 1812 revisions of his first book, “A History of New York.” In one section, Irving created a dream sequence involving Saint Nicholas, whose name in Dutch is pronounced “Sinterklaas.” Irving had Saint Nicholas flying through the air over Manhattan in “the self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children.” The Saint descended to the ground to smoke his pipe and then, “laying his finger beside his nose (and) mounting his wagon, he returned over the treetops and disappeared.”

Researching ancient Christmas customs

In 1815, Irving moved to Europe and began researching ancient Christmas customs in that country’s libraries and museums. He synthesized those findings into five chapters of a 34-chapter collection of essays published in 1819 as “The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon.” Later broken out as the separate illustrated book, “Old Christmas,” the heartwarming tale has remained in print for two centuries.

It’s an account of the fictitious Geoffrey Crayon’s Christmas-time visit to the fictitious baronial estate “Bracebridge” in a remote part of Yorkshire in northern England. There, a family of the same name had doggedly maintained the old Yuletide rituals long abandoned by the rest of the country. “There is nothing in England that exercises a more delightful spell over my imagination than the lingerings of the holiday customs and rural games of former times,” writes Irving in the opening paragraph of “Christmas,” the first chapter of “Old Christmas.”

The quest to find and explore those old ways begins in earnest early on a snowy Christmas Eve in chapter two, “The Stage Coach.” After many hours of traveling through bucolic winter landscapes and quaint villages, Irving’s protagonist stops at a stage coach tavern hung with greens, warmed by a crackling fire and filled with the good cheer of a crowd headed to their final Christmas destinations.

Wilson-Warner mansion event

This pivotal tavern scene also opened the Odessa Wilson-Warner mansion’s Old Christmas exhibit, turning the house’s rear kitchen area into a stagecoach inn. It was one of five rooms depicting each of Irving’s five chapters. Lit by candlelight, its main table was spread with plates of Cornish pasties, oysters, bread, cheese and tankards of ale. A Christmas pudding sits alluringly near a lantern nearby. Closer to the fireplace is a nest of cozy seats like those in which Irving’s Crayon encountered an old acquaintance, Frank Bracebridge, who was traveling home to spend Christmas at his family’s Bracebridge estate. He explains that his father, the Squire, is a “bigoted devotee” of the old school of Christmas merriment and invites Crayon to accompany him home to be part of that old-time holiday experience.

They arrive at the snow-covered Bracebridge estate after dark and are quickly ushered into a hall where a flaring Yule log and special Christmas candles stand sentry over a high-spirited crowd in which servants and workers easily mingle with family members and relatives. In a din punctuated by frequent laughter and shrieks of excited children, all gorge on mince pie and spiced wines as they deal cards, play floor games, sing the traditional carols, applaud the musicians, and regale each other with tales of Christmases past.

To capture this scene, Historic Odessa’s crew emptied the second story master bedroom of the Wilson-Warner house and re-envisioned it as a small hall and gaming room. There, a flock of 18th-century card tables were lit by candles and set with plates of sweets, nuts, cheeses and fruits and casually littered with the clay pipes and colorful fabric pocketbooks of gentlemen who have momentarily left the room.

Overhead hung a large cluster of white-berried mistletoe that, as Irving noted, presented an “imminent peril” to all the young ladies. The musicians’ pianoforte, violin, guitar, mandolin, penny whistles and flutes stood at the ready while wooden toys of exuberant children lay scattered at the room’s corners. Later in the evening, the tables are folded away to the side of the room, freeing the floor for the dancing that goes on in the book into the wee hours.

For the “Christmas Dinner” chapter, Odessa’s Wilson-Warner house transformed its dining room into a tableau of the feast Irving’s book situated in the Squire’s great hall — where the walls were hung with portraits of ancestors dating back to the time of Henny VII. A similar phalanx of 18th-century portraits lined the Wilson-Warner walls, looking down on the two most striking features of that dining room’s faux feast that mimicked Irving’s account: a grand peacock pie in the center of the table and a roast pig’s head glistening on its sideboard tray nearby.

In the Squire’s great hall, the silver Wassail bowl was ceremoniously passed from hand to hand as guests drank directly from the vessel. Many of the women kissed the rim coyly before drinking. It was, wrote Irving, “the ancient fountain of good feeling, where all hearts met together.”

As his narrative ends on Christmas evening, Irving says he hopes his five-chapter tale has at least amused readers and perhaps inspired some of them to be “more in good humor with his fellow beings” at Christmas-time, proving that the author had not “written entirely in vain.”

First American international best-seller

On that score, Irving succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. His “Sketch Book” catapulted him to celebrity and a distinctive place in history as both the new Republic’s first internationally best-selling author and the man who began the populist resurrection of the traditional English Christmas; his story of ‘Bracebridge’ started the trend Clement Clark Moore, Charles Dickens, Thomas Nast and others embellished and promoted into the Christmas customs Americans hold most dear today.

“We’ve been doing this for a lot of years, but I think this Washington Irving exhibit has been one of the best,” said Foundation executive director and curator Debbie Buckson. “Irving’s writing is so detailed; when that written word was coupled with Randolph Caldecott’s illustrations from the later ‘Old Christmas’ edition, it gave us a story of great depth and equally great visual material to work with. It just doesn’t get better than that.”

The Historic Odessa Foundation’s tradition of annual “literary Christmas” exhibits began in the early 1980s. Twenty years earlier, the local Women’s Club began promoting “Christmas in Odessa” tours of residences outside the historic district. At the time, the Foundation’s houses in the historic district strictly interpreted the homes of Quaker families that did not celebrate Christmas.

Reversing a policy

“People were disappointed,” said Buckson, a former director of events and programs at Delaware’s Winterthur Museum, “They expected to see something like grand Williamsburg holiday style but ended up walking through rooms that were historically accurate but not decorated.”

The frustration of those thousands of visitors who flocked to the town’s annual tour caused the Foundation to rethink its position. “We wanted to remain true to our scholarly roots at the same time we wanted to support the community’s holiday activities,” Buckson said. “It occurred to us that we COULD give the public Christmas and stay true to our roots if we used one of our buildings to interpret Christmas literary traditions themselves. The first one we tried was ‘A Visit From Saint Nicholas.’ Visitors loved it and, so, we’ve continued to do it ever since.”